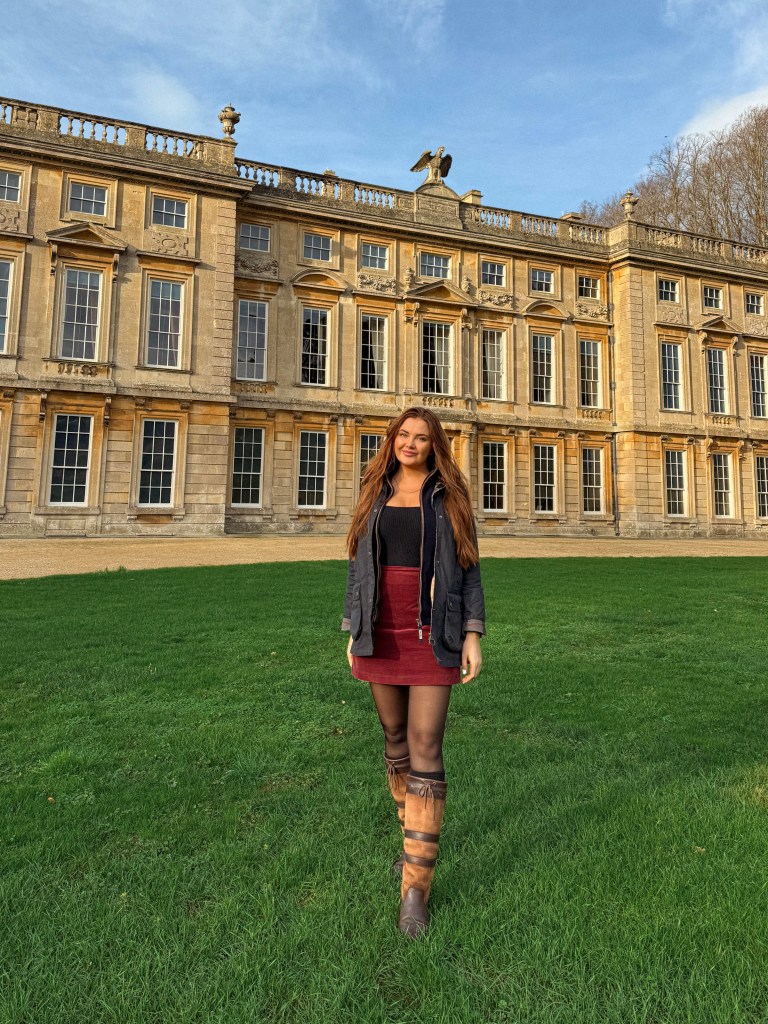

Despite being a Bath local since April, I must confess to a small but significant folly: delaying my first visit to Dyrham Park, a mere twenty-minute drive from the city. No matter the season or the weather, one can’t go wrong with 270-acres of landscaped parkland and Baroque architecture.

A house of Baroque Ambition

Dyrham dates back to Medieval times, having been recorded in the Domesday Book. However, by 1704 following extensive remodelling by Samuel Hauduroy and William Talman to align it to Baroque styles, little of the Tudor house remained beyond the Great Hall.

If you’re an ‘aristourism’ enthusiast like me, you might notice that the facade looks similar to Chatsworth House – which is no surprise as Talman had earlier rebuilt Chatsworth’s grand south and east fronts in the 1690’s, while serving as Comptroller of the Royal Works under William of Orange.

The warm limestone house is nestled serenely in a quiet valley, yet on approach one is met with a regiment of sash windows and an authoritative stone eagle surveying from above. Talman’s addition of an orangery to the south front, inspired by Versailles, speaks to the estate’s royal aspirations.

Dyrham’s most influential owner

William Blathwayt obtained the property from his fortuitous marriage to Mary Wynter, heiress of the Dyrham estate. Raised by his uncle Thomas Povey after his father’s death, Blathwayt was educated in diplomacy, finance, and the arts, and trained from a young age in the mechanics of government.

He rose rapidly through the ranks, overseeing the army, managing the diplomatic service, and directing colonial affairs. He served under King James II up until he was overthrown by King William of Orange, and despite his Jacobite leanings was re-employed by the new king as Secretary of State – effectively the administrative engine of the Crown.

Blathwayt’s mastery of detail, fluency in Dutch and constant proximity to power gave him exceptional influence across military, financial and colonial policy at a time when England’s empire was rapidly expanding, particularly across the Carribean, and North America.

Though never a peer (likely due to accusations of being a Jacobite), he was one of the most influential administrators of the early English Empire, playing a pivotal role in shaping colonial governance.

He was deeply involved in managing correspondence between Whitehall and colonial officials, resolving disputes, and ensuring that imperial policy aligned with England’s strategic interests against rival European powers, particularly France and Spain. Later in life he also served as a Bath MP, holding the seat until his retirement.

Dull-Defying Interiors

Although Blathwayte was described by William III as ‘dull’ company, the house tells a very different story. Blathwayte spared little expense, furnishing Dyrham with imported marbles, exotic woods, silks, delftware and fine art. Oak wainscoting, walnut panelling, tapestries and leather-hung walls add to the measured ostentation. Remarkably, little of the interior has changed, leaving Dyrham to boast one of the best surviving Baroque interiors in the country.

Much of the house’s artistic richness can also be traced to Blathwayt’s purchase of his uncle Thomas Povey’s art and book collections. Povey, who raised Blathwayt as his own son after his father died, was instrumental in shaping his career in government and colonial administration. Through Povey, important works by Samuel van Hoogstraten found their way to Dyrham, such as the clever perspective painting in the doorway below.

From Private Home to National Heritage

Dyrham remained in the Blathwayt family until the mid-20th century. Its last owner, Justin Robert Wynter Blathwayt (1913–2002), sold the estate in 1956 in the face of heavy death duties and the mounting cost of upkeep. The property passed to the Ministry of Works and was later transferred to the National Trust, which opened it to the public in 1961.

Now, having painted such a flattering picture, here’s a pinch of salt. This may be the first house where one encounters quite so many trigger warnings before entering a room. While it’s clear that Blathwayt benefited from managing Britain’s colonial empire, I felt that the emphasis was heavy handed and distracted from the broader story of the house and its collections. For instance, I found hardly any information about his relationship with two rival monarchs and his ‘House-of-Cards’ style navigation of politics. There was also a distinct lack of objects on display compared to some other properties I’ve visited, but perhaps they are being restored.

I also visited during Christmas and found some of the decor to be rather tacky, wrapping beautiful antique globes in the ugliest tinsel they could find and paper Christmas hats stuck on portraits in the entrance, but otherwise the Christmas trees and decorations outside were quite tasteful.

The cafe, as with any National Trust cafe, also leaves much to be desired and the second hand bookshop has been raided harder than Russia during the Mongolian empire..

Neverthelsess, Dyrham Park today stands as a deeply pleasurable place to wander, and a compelling testament to Baroque ambition and imperial history. For anyone within reach of Bath – or indeed further afield – it is a reminder that some of the most extraordinary places are hiding just around the corner, patiently waiting to be discovered.

Leave a comment